Among the Grassy Knoll Left, the CIA has always been the prime suspect in the JFK assassination. In their scenario, the Agency had good reason to kill the president as his supposed attempts to end the Cold War threatened the justification for their existence and the source of their sinister power. With the president who represented the “last best hope” in checking this American version of the SS murdered, the CIA continued unchecked its shadowy control of the United States government.

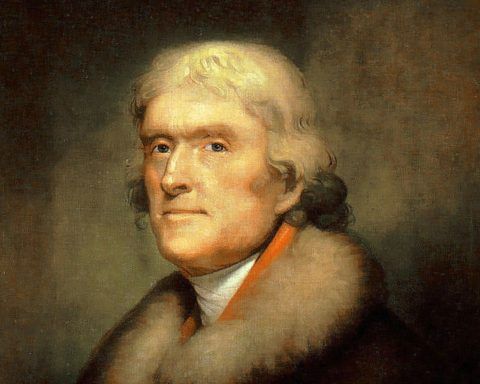

Despite being a conspiracy theorist himself, Jefferson Morley, nevertheless keeps his head about the Agency in this good but occasionally frustrating biography of its Chief of Counterintelligence James Angleton. The CIA that emerges in this work is far from the “fascist security state” characterization peddled by Oliver Stone (whose film JFK Morley admires) but is instead populated by the same type of liberal anti-Communists that JFK embodied.

Thus, despite JFK’s declaration after the Bay of Pigs “to splinter the CIA in a thousand pieces,” Morley shows a warm relationship between the president and the Agency in their shared goals of toppling Castro without resorting to war; by turns, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, one of Morley’s villains in the book, demanded a full scale invasion and regarded Kennedy’s refusal to do so as borderline treasonous.

Angleton shared the latter view and despite a Yale background and service to the OSS never really fit in with the Agency. Ideologically, he was far from being liberal anti-Communist, and instead had fascist leanings; imbibed while a college student majoring in literary criticism at the feet of his guru, Ezra Pound, and later demonstrated when, as a fledgling CIA agent, he provided a safe haven and hefty stipend for Nazi war criminals.

In the hands of the CIA-bashing Kennedy Conspiracy group such a portrait made Angleton the perfect suspect. But Morley resists such an ideologically satisfying culprit.

Instead, he confines his accusations against Angleton to his lying to the Warren Commission that he knew nothing about Oswald until the day of the assassination. Morley skillfully invalidates this claim, showing that Angleton had opened a file on Oswald as far back as 1959 and updated it all the way up to 1963.

Morley also entertains the possibility that Cuban intelligence guided Oswald into murdering the president by blasting Angleton for not following up on these promising leads.

Morley concludes the book with the assertion that for the first half of his career Angleton “ably” protected America from its enemies. But nothing of this sort emerges in his portrait. Instead the reader is presented with an Angleton who violated the Constitution by engaging in overseas’ wet-work and opening the mail of and spying on ordinary citizens.

And Angleton doesn’t emerge from this work as very good at this job. His hyper-paranoia resulted in a disastrous mole hunt within the Agency that nearly wrecked it. By the early 1970s, Angleton’s accusations were no longer confined to his fellow employees, but were now including Secretary of State Henry Kissinger whose “détente” policies were supposedly part of a Soviet plot. He was only stopped with the appointment of William Colby, an authentic liberal, to head the CIA. In many ways the hero of this book, Colby, in order to achieve his desires to make the CIA in the wake of Watergate more accountable to the public, had no other alternative than to force Angleton into retirement.

On the basis of effectiveness, the figure who emerges as more worthy of this characterization is CIA agent William Harvey, the bane of Camelot historians and one of the Grassy Knoll’s favorite suspects. While Angleton was having boozy lunches with Kim Philby where intelligence information flowed as freely as the liquor, Harvey early on knew that Philby was a Soviet mole and was instrumental in getting Philby kicked out of the US and out of Angleton’s intelligence loop in 1951. Meanwhile Angleton remained in denial about Philby until the latter validated Harvey’s beliefs by defecting to Moscow in 1963.

And while Angleton was wasting time and resources on bizarre schemes to hypnotize a person into murdering Castro, and in fruitlessly trying to prove that a Soviet mole, who he kept under harsh conditions for 4 years, was a false defector, Harvey was doing the real work of the Cold War. His tunneling into East Berlin that enabled Harvey to tap their phone systems provided the Agency with valuable intelligence.

The weakness of this book, however, is the information he doesn’t give the reader; chiefly by ignoring the very real Soviet penetration of the government that made Angleton’s paranoia understandable. Throughout the book there is no mention of atomic spy Julius Rosenberg or Alger Hiss, the latter of whom occupied such a high position in the State Department that he was the chief advisor to FDR at the disastrous Yalta accords. Because of their insane denials of Soviet espionage even when confronted with inconvertible facts, it is apparent that a more thorough investigation of those proclaiming innocent was warranted by the author.

That said Morley does make his case that Angleton was a dangerous and counter-productive paranoiac responsibly and empirically.

For future writers of the CIA in general and the Kennedy assassination in particular, Morley’s biography should stand as an example of writing only what is provable and not what is ideologically satisfying.