There’s an old saying that “he who distinguishes well teaches well.” In other words, if one’s going to talk about an important subject, one should be able to define his terms and tell the difference between two things that are not the same.

This wisdom, unfortunately, is rarely embraced by modern pundits arguing about the causes of the American Civil War. A typical example can be found in this article at the Huffington Post in which the author opines: “This discussion [over the causes of the war] has led some people to question if the Confederacy, and therefore the Civil War, was truly motivated by slavery.”

Did you notice the huge logical mistake the author makes? It’s right here: “…the Confederacy, and therefore the Civil War….”

The author acts as if the mere existence of the Confederacy inexorably caused the war that the North initiated in response to it. That is, the author merely assumes that if a state secedes from the United States, then war is an inevitable result. Moreover, she also wrongly assumes that the motivations behind secession were necessarily the same as the motivations behind the war.

But this does not follow logically at all. If California, for example, were to secede, is war therefore a certainty? Obviously not. The US government could elect to simply not invade California in response.

Moreover, were war to break out, the motivations behind a Californian secession are likely to be quite different from the motivations of the US government in launching a war. For the sake of argument, let’s say the Californians secede because they couldn’t stand the idea of being in the same country with a bunch of people they perceive to be intolerant rubes. But, what is a likely reason for the US to respond to secession with invasion? A US invasion of California is likely to be motivated by a desire to extract tax revenue from Californians, and to maintain control of military bases along the coast.

Thus it would be absurd to equate the motivations of the California secessionists with those of the advocates for the invasion of California.

To put it simply: an act of secession, and a war that may follow it, are not the same thing.

And yet we find that commentary on the Civil War repeatedly conflates secession with the Civil War itself as if they were exactly the same thing.

But before we go any further, let’s get this out of the way: the secession movement itself was obviously motivated by a desire to maintain slavery. This is easy enough to show because many Southern secessionists explicitly said so in their declarations of secession. In the South Carolina declaration of independence, the entire second half of the document explains that the state is seceding because it fears the North will force emancipation on the country as a whole. The authors of the document denounce Northerners for electing a president who is “hostile to slavery” and for a “current of anti-slavery feeling” that allegedly pervaded the North at the time. What especially annoyed the secessionists was the North’s refusal to enforce the federal fugitive slave laws against abolitionists who “encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves” in escaping slavery.

The Mississippi declaration went even further, equating slavery with civilization itself, and claiming “a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization,” and plainly states that “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery — the greatest material interest of the world.”

In both of these documents, taxes and free trade are barely mentioned. Slavery was clearly at the heart of the matter, which is in part why British free-trade crusader Richard Cobden rejected claims that the South had seceded primarily over tax and trade concerns.

None of this means the war was motivated by slavery or opposition to the institution. After the fact, opponents of slavery claimed the war was about emancipation, which it clearly was not, except in the minds of a small minority of radical Republicans. It was not until military victory was apparent that the Republican leadership began to press for nationwide emancipation in negotiations with the South.

Almost until the end, the war was motivated by a concern for preserving tax revenues, and by nationalism. In a North where few people were full-on abolitionists, very few were willing to run off and stop a bullet to end the institution of slavery. Even those who disliked slavery were not exactly rushing off to shoot people over the matter. New York attorney George Templeton Strong’s attitude in 1861 toward Southern secession was one of “good riddance.” Referring to slavery as the “national ulcer,” Strong concluded that “the self-amputated members were diseased beyond immediate cure, and their virus will infect our system no longer.” Strong noted that his impression of Northerners was that they were granting “cordial consent” to Southern secession.

Those who were ready to call for war were more often animated by ideological views tied to defending “the Union,” which many regarded as sacred, while the Northern policymakers themselves were concerned with the retention of military installations and with revenue concerns. The South provided a lot of revenue for the North, and the North wanted to keep it that way.

Years into the war, many Americans were still perfectly happy to come to a negotiated settlement with the South that allowed for the continuation of slavery. Indeed, in the 1864 election, the Democratic nominee, who promised to end the war without abolishing slavery, won 45 percent of the popular vote. (Voters in Confederate states were excluded, of course.)

Should the North have invaded the South to end slavery? That’s a separate question, and one that is also totally distinct from the question of secession. Northern armies could have invaded the South at any time to force emancipation on the South. No secession was ever necessary or key to the equation.

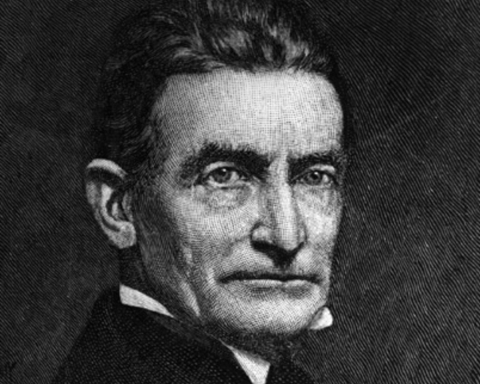

The lack of precision used in equating the war, slavery, and secession, serves an important purpose for modern anti-secessionists. Their knee-jerk opposition to any form of decentralization or locally-based democracy impels them to equate secession itself with slavery, even though secession can be motivated by any number of reasons. After all, secession was the preferred strategy of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison who as early as 1844 began preaching the slogan “No union with slaveholders!” In Garrison’s mind, the North ought to secede in order to free northerners from the burdens of the fugitive slave acts, and to offer safe haven to escaping slaves.

Had such a scheme played out, and the South had taken military action to force the North back into the union, would we be hearing today about how the only appropriate response to secession is open warfare? One would certainly hope not.

One key point that some of the sons of the South keep trying to deny is that secession wasn’t about slavery. As you point out, THEIR OWN DECLARATIONS OF SECESSION mention slavery, Georgia the most clearly. The only mention of taxation is the use of the same 3/5 person for slaves to apportion taxes as representation. I have yet to see ANY official document saying otherwise. Yes, they didn’t like the tariffs, but then why wasn’t that in any of the secession declarations? Meanwhile up North, Lincoln supported the Corwin amendment, enforced the Fugitive Slave Act, and worse. Yes, the first casualty in war is the truth.

Except the war didn’t start with secession. Most of the South had already seceded and the Confederacy had already formed before Lincoln even took office. The problem was that the Confederacy wasn’t recognized as an independent country. They had a couple ways to get recognition: A) elect Congressmen and appoint Senators who would push for Congress to recognize their new nation B) start shooting at US troops who were already stationed there. They chose B.